When You Rescue Markets

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

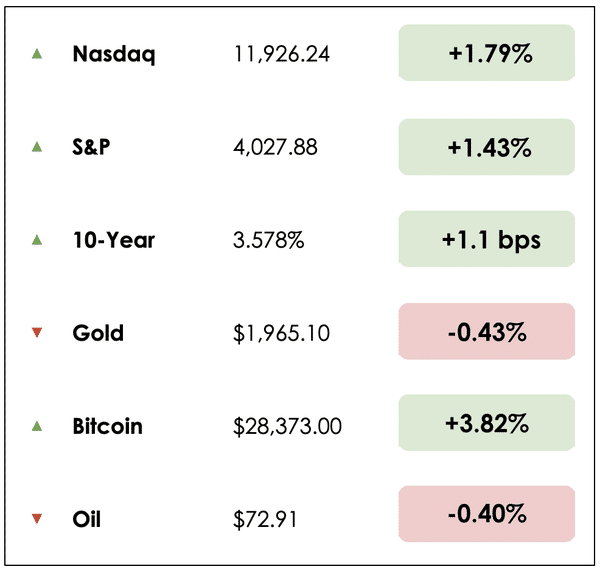

Market jitters seem to be easing: The CBOE Volatility Index, aka the VIX, or as some say, “Wall Street’s fear gauge,” fell to around 19 on Wednesday.

That’s down from over 26 at the peak of recent banking turmoil. The VIX is derived from the prices of options on the S&P 500 about one month out, reflecting expected price volatility.

To that point, First Republic Bank, feared to be the next to fall before liquidity injections from the nation’s biggest banks boosted its prospects, rallied 5.6% today 📈

Here’s the rundown:

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news:

- The global rice crisis, explained

- What happens when you rescue markets

- Plus, our main story devoted to simply outlining the recent banking crisis

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Understand the financial markets

in just a few minutes.

Get the daily email that makes understanding the financial markets

easy and enjoyable, for free.

Real estate investing, made simple.

17% historical returns*

Minimums as low as $5k.

EquityMultiple helps investors easily diversify beyond stocks and bonds, and build wealth through streamlined CRE investing.

*Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. Visit equitymultiple.com for full disclosures

IN THE NEWS

🍚 Global Rice Crisis (Economist)

Explained:

- Rice feeds more than half the world. It’s especially beloved in Asia, where rice is conferred with a divine, and usually feminine, origin story. But it’s been proven to fuel diabetes and climate change.

- Global rice demand—in Africa as well as Asia—is soaring. Yet yields are stagnating. The land, water, and labor that rice production requires are becoming scarcer, climate change is a threat, rising temperatures are withering crops, and more frequent floods are destroying them.

- Further, rice isn’t just a victim of climate change; rice cultivation is a cause of it, because paddy fields emit a lot of methane, the potent greenhouse gas that cows generate.

- The global rice market was nearly $300 billion in 2021, compared with $81 billion for pasta and noodles.

Why it matters:

- Rising demand exacerbates the problem. By 2050 there will be 5.3bn people in Asia, up from 4.7bn today, and 2.5bn in Africa, up from 1.4bn. That growth is projected to drive a 30% rise in rice demand, according to a study published in the journal Nature Food.

- Yet Asia’s rice productivity growth is falling. Yields increased by an annual average of only 0.9% over the past decade, down from around 1.3% in the previous decade, according to data from the UN. The drop was sharpest in southeast Asia, where the rate of increase fell from 1.4% to 0.4%.

- Indonesia and the Philippines already import a lot of rice. If yields do not increase, these countries will be increasingly dependent on others to feed their 400m people, according to the Nature Food study

🚑 When You Rescue Markets (WSJ)

Explained:

- Bailing out the financial system in times of crisis can have unintended consequences. First, making the world feel safer can lull people into complacency and excessive risk-taking. (Sound familiar?)

- This month, U.S. authorities promised to back uninsured deposits at the failed Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. They also created a new program to lend up to $25 billion to other banks with shaky balance sheets. The message: Don’t panic.

- But as researchers have pointed out, making an environment feel safer can lull people into complacency and coalesce power into a few people’s hands at the financial system’s pinnacle.

- Among the most notable interventions from the Fed and the Treasury: in 1998, a $3.6 billion rescue of the hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management; in 2001, slashing interest rates to reassure investors after internet stocks collapsed; in 2008-09, buying money-market funds with up to $50 billion and pouring more than $425 billion into banks.

Why it matters:

- Unfortunately, having some sway over markets can delude regulators and policymakers into believing they can foresee the future. “We believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will likely be limited,” then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said in a speech in May 2007, “and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system.”

- The spillovers were significant enough to cause the global financial crisis of 2008-09. Another example: Top officials at the Fed said inflation was “expected to be transitory” as late as November 2021, months after the cost of living had hit its highest rates of increase in 13 years.

- Only a few months later, inflation peaked at 9.1% and has proven sticky 15 months later. “We’re not thinking about raising (interest) rates,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell said on June 10, 2020. “We’re not even thinking about thinking about raising rates.”

- Writes Jason Zweig of The WSJ: “Central authorities aren’t omniscient and omnipotent, and their efforts to wring risk out of the system may make it more dangerous, not less.” More on bank crises and market rescues below.

RECOMMENDED READING

From our good friends at the Top Traders Unplugged podcast, check out their Ultimate Guide to the Best Investment Books of All Time, featuring over 300 handpicked titles that are bound to transform your investing journey.

The best part is — it’s absolutely FREE to download right now!

But that’s not all. As a valued member of The Investors Podcast’s community, there’s something a little extra just for you. When you download the guide, you’ll also receive an exclusive bonus as a token of our appreciation.

Grab these incredible resources and watch your investing knowledge soar to new heights:

WHAT ELSE WE’RE INTO

📺 WATCH: Beyond ChatGPT — what chatbots mean for the future

👂 LISTEN: Why the legacy banking system is in shambles

📖 READ: Shohei Ohtani is set to make $65 million next season, a Major League Baseball record

Bank failures

Last week, I (Shawn) had the opportunity to discuss the recent banking crisis with my colleague Clay Finck on the We Study Billionaires podcast, which aired on Monday.

It’s an important topic, and we cover a lot in the episode, so I’d like to walk through some of the most important takeaways.

What to know

Starting from the beginning, the first bank to go down was Silvergate on Wednesday, March 8th. This sparked fears that brought down two more banks over the next four days: Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank.

Unlike 2008, where banks nearly destroyed the global economy due to malinvestment in toxic, difficult-to-value assets, these banks fell for very different reasons: record interest rate hikes after years of artificially low rates and a lack of depositor diversification.

In fact, the asset holdings that caused them trouble were supposed to be the safest — U.S. government bonds.

Of course, these banks’ executive teams are also guilty of risk management mistakes, but these were the two structural challenges that they fell prey to.

Let’s break down those two points.

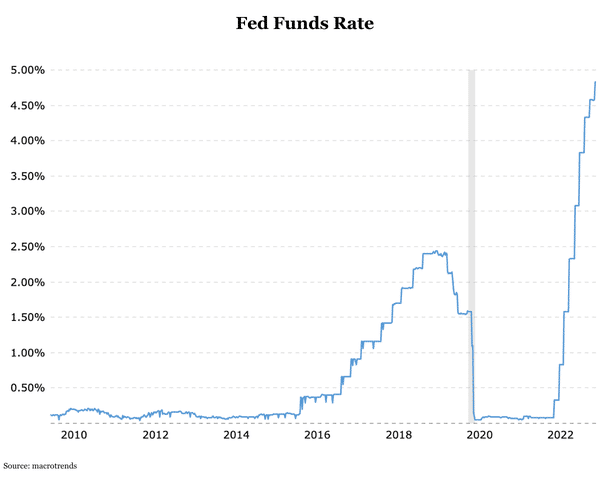

Record rate hikes

Because of their connections to fast-growing industries like crypto and the venture capital space, these banks saw huge surges in deposits.

SVB, for example, saw its balance sheet triple between late 2019 and early 2021. While business was booming, the timing was far from ideal.

That’s because they were flush with cash and had to find something to do with it at a time when “safe” assets like government bonds were at record-high prices.

Bond prices and interest rates have an inverse relationship, so when the Fed cut interest rates to stimulate the economy during the Covid pandemic, they correspondingly boosted prices for U.S. Treasury bonds.

SVB, in particular, piled into long-dated Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, only to see the Fed undergo its largest rate-hiking fight against inflation in four decades. As the Fed pushed rates higher in 2022, its bond portfolio fell in value.

When SVB was forced to sell $1.8 billion worth of its bonds at a loss to meet withdrawal requests, investors realized that not only was SVB in trouble, but many other banks might be due to large holdings of bonds bought during the low-rate Pandemic times that had since lost value.

Some estimates, as shown in the image below from Axios, say that U.S. banks have over $600 billion in unrealized losses on bond holdings.

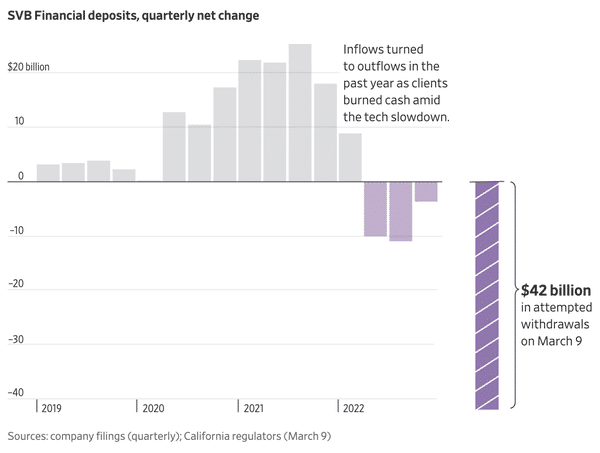

Deposit concentration

The other issue, as mentioned, was a lack of depositor diversification, which forced these banks to sell assets at a loss.

In that regard, Silvergate and Signature were overexposed to crypto firms.

When crypto business was booming for these companies in 2021, the banks did great, too. But as the Fed pushed up interest rates, the opportunity cost for owning more speculative digital assets rose since investors could get guaranteed 4-5% returns on government bonds.

That wiped out trillions of dollars in market value for digital assets and destroyed many companies across the space, who spent down their cash balances held at these banks, forcing banks to sell assets to provide depositors their money.

For SVB, it was a similar story, just with venture capital (VC) firms, where they had built a reputation as the go-to bank for servicing young businesses. On paper, their depositor base looked diversified, servicing thousands of companies.

In reality, most of these firms were backed by a handful of large VC investors, who sparked a bank run when they realized SVB’s deteriorating financial position and told their portfolio companies to withdraw funds.

Was this a bail out?

Strictly speaking, this wasn’t a tax-payer-funded bailout because the funds are coming from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which raises the money from fees charged to licensed banks that must pay into its insurance fund.And regulators quickly pointed out that the management at these banks were terminated and that their stocks were now worth zero, so it wasn’t a shareholder bailout, but a depositor bailout, backed by the entire banking system essentially.

Pointing fingers

Things have stabilized (for now), and regulators are sifting through the fallout to better understand what happened.

In Congressional hearings yesterday, the Fed’s vice chairman for banking supervision, Michael Barr, suggested, “Fundamentally, (SVB) failed because its management failed to appropriately address clear interest-rate risk and clear liquidity risk.”

He added, “Essentially, the risk model (at SVB) wasn’t at all aligned with reality.” Ironically, that troublesome reality is one the Fed created with its rate hikes, while the bank generally held the sort of assets (government bonds and government-backed mortgage securities) that regulators would encourage.

SVB failed to manage its exposure to these assets and took on too much of what’s known as duration risk, but the notion that banks could fail from having too many “safe” assets on their balance sheets stands distinctly in contrast to the banking meltdowns in 2008.

Dive deeper

To hear Clay and I’s full conversation on the banking crisis, you can listen to the episode here.

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

Enjoy reading this newsletter? Forward it to a friend.