The Cost of Democratizing Finance

17 February 2023

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

82% of companies in the S&P 500 have reported their fourth-quarter earnings, and the results aren’t amazing — 68% of companies beat Wall Street’s earnings estimates, below the five-year average of 77% 🏳️

Profits declined nearly 5% from last year. For the 85 S&P 500 companies that offered earnings forecasts, 76% came in below consensus expectations.

🏖️ Quick note: We’ll be off for Presidents’ Day on Monday, but we’ll be in your inbox on Sunday and back again Tuesday.

Enjoy the long weekend!

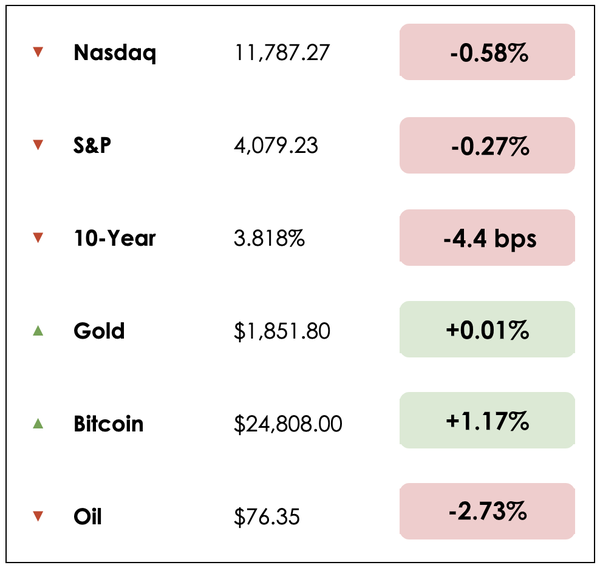

Here’s the market rundown:

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news:

- The big business of school safety

- Americans can’t get enough of food delivery services

- Plus, our main story on how passive investing impacts investment returns

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Get smarter about valuing businesses in just a few minutes each week.

Get the weekly email that makes understanding intrinsic value

easy and enjoyable, for free.

IN THE NEWS

🍜 Consumers Love Delivery (WSJ)

Explained:

- DoorDash (DASH) sales rose last quarter as people kept spending more on food delivery, even as prices rose.

- DoorDash’s revenue in the three months through December grew 40% to $1.8 billion from a year earlier. Analysts surveyed by FactSet had predicted revenue of $1.77 billion. The company said it ended 2022 with a record 32 million monthly users and that its subscription service DashPass now has more than 15 million members, up from 10 million a year earlier.

- “Despite what’s going on in the broader macroeconomy, we’ve delivered double-digit growth over the last seven quarters,” said Ravi Inukonda, vice president of finance and strategy.

Why it matters:

- DoorDash said its fourth-quarter revenue was lifted by strong consumer demand, in part due to improved delivery speeds. It benefited from having more DashPass subscribers, and total orders on the app grew 27% to 467 million.

- Orders for delivery companies DoorDash, Uber Technologies Inc.’s Uber Eats and others skyrocketed during the pandemic as people avoided going out to restaurants.

- While the two largest food-delivery apps in the U.S. are still growing, the pace of growth has cooled in recent months. The companies face soaring inflation that’s crimping consumer spending power. Yet many people still want food delivered, even if they’re paying more.

🏫 The School Safety Sales Pitch (NYT)

Explained:

- Preparing schools for mass shootings is becoming routine in America, and now school safety has become a sales pitch.

- For example, Armoured One is a New York state-based company that sells protective glass and film. Founder Tom Czyz has given demonstrations to school officials, including firing more than 30 rounds at a window at close range. It typically costs about $350 to install an Armoured One protective window in a classroom door, which Czyz said could slow down someone trying to shoot his way into a locked room.

- Mass shooting preparedness companies are popping up nationwide. Offerings include automatically locking doors, bullet-resistant tables, Kevlar backpacks, artificial intelligence that detects guns and countless training exercises, like breathing techniques to avoid panic during an attack or strategies for using a pencil to pierce a shooter’s eyes.

Why it matters:

- Rising gun violence, punctuated by massacres like the attack at the elementary school in Uvalde, Texas last year and the shooting on Michigan State University’s campus this week, is fueling not only the debate over gun control but also a more than $3 billion industry of companies working to protect children or employees against mass murder.

- But even as Congress increases funding for school security measures — including $300 million to help schools “prevent and respond to violence” as part of a bipartisan gun control compromise — the effectiveness of the school security industry’s products and services remains largely unproven.

- In a survey of more than 1,000 public schools last year by the National Center for Education Statistics, a research arm of the Education Department, the majority said they were taking some measures, such as putting locks on doors, to defend against shooters. As the threat of violence grows, so is the industry offering ways to stop it.

WHAT ELSE WE’RE INTO

📺 WATCH: Warren Buffett’s $4 billion pivot, with Weronika Pycek

👂 LISTEN: How to become your own bank and build wealth like the 1%

📖 READ: Microsoft’s AI chatbot “wants to be human“

Democratized finance

Sure, investing has become more accessible over time, but is that a good thing for investors at large?

Obviously, having ownership of the world’s largest corporations concentrated in only the upper echelons is problematic.

Is the other extreme any better, though?

What if 100% of society was broadly invested in stocks using ever cheaper and more accessible index funds?

It’s a world we’re increasingly trending toward: For most, making a new investment is just a matter of a few clicks on their mobile device, while major exchange-traded funds (ETFs) offer access to hundreds, sometimes thousands, of underlying stocks in a single security, often known as index funds.

Breaking it down

Bloomberg’s Matt Levine explains the issue: “An index fund is a good way to own stocks; it has low fees and offers diversification. Therefore, if index funds are easy and cheap, more people will invest in the stock market than if there were no index funds. This will push up the price of stocks, pushing down their expected returns. Therefore, index funds are bad for investors.”

And this isn’t a particularly controversial point, either. Over time, stock returns are principally driven by earnings growth.

In other words, stock prices fluctuate dramatically over months and even years. Still, share price appreciation in the long term is driven by rising earnings. Greater profits enable companies to develop more valuable assets (from effective reinvestment) and earnings power, or at least accumulate more capital to return to shareholders.

This all makes the underlying shares more valuable than before, because they now represent a slice of a bigger pie (of current or future earnings).

As more capital flows into stocks broadly from new investors via index funds who otherwise might not be invested, prices are bid up for ownership in the same businesses and their corresponding profits.

The math

Naturally, your future percentage returns will be lower if you pay more for equity shares today relative to companies’ per-share profits. This is why people spend so much time looking at price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios — they’re a rough indicator of future returns.

The S&P 500 aggregate P/E ratio is roughly 22, meaning buying an ETF tracking the index would translate to paying $22 for $1 of earnings from America’s 500 largest companies.

If we pay $22 per share for $1 in profits, we should expect at least a 4.55% return annually, that is, one divided by 22.

To Levine’s point, if larger swaths of society participate in the stock market, greater inflows will drive up prices and, correspondingly, P/E ratios, which pushes down future returns. For example, if in a decade from now, the S&P 500’s P/E ratio rises to 30, then expected returns drop to 3.33% (1 divided by 30).

Splitting up the pie

In simpler terms, if we hold everything else constant, as more people search for financial freedom through the promise of stock investing, investors are collectively worse off, earning lower and lower percentage returns relative to the growing percentage of society engaged in equity markets.

In a recent study, “Index Funds, Asset Prices, and the Welfare of Investors,” Martin Schmalz, a professor of finance and economics at Oxford, confirms this problem and explores the social and investment outcomes of the democratization of financial markets.

Today, about 50% of Americans have a significant chunk of their savings invested in diversified stock funds, with return expectations ranging from 5-7% yearly.

If only 25% of society were invested, you could pay a lower premium (lower P/E ratio) for ownership in America’s best companies, providing returns closer to, perhaps, 12% — hypothetically speaking. On the other end of this spectrum, with 100% of society invested, future returns might fall to 3-4% or less.

More people are getting a slice, but everyone’s piece (of returns) is reduced.

Schmalz argues it’s a “tragedy of the commons problem,” where financial returns are the common resource everyone is tapping into and depleting.

For individuals, investing in stocks and owning index funds is typically the best thing to do, which is the problem, because if everyone does that, the promised rates of wealth compounding derived from historical return data become less obtainable.

Who wants to tell grandma that her nest egg might generate far lower returns than her financial advisor has promised her?

What, then, should we do?

Few are going to “take one for the team” and offer to try picking their own stocks or even stop investing in stocks altogether to boost the financial returns available to the rest of society.

If you want to save for your retirement or your kid’s college fund, well, you’re probably going to buy an extremely low-cost index fund that offers exposure to thousands of stocks. Yet, you now know, or already knew, about the tragedy of the commons dynamic from this.

Technology has delivered the prospect of financial inclusion to the masses, potentially reducing overall inequality while pushing up asset prices and lowering expected future returns.

Dive deeper

To hear Schmalz describe the challenges that passive index investing is creating at scale, listen to his Bloomberg podcast interview here, or check out his full research paper.

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

See you later!

If you enjoyed the newsletter, keep an eye on your inbox for them on weekdays around 6pm EST, and if you have any feedback or topics you’d like us to discuss, simply respond to this email.