Borderline Fraud

9 September 2022

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

Welcome back to We Study Markets!

Patrick’s out today but for good reason — He’s getting married 🎂

Despite Fed hawkishness, markets are still predicting the Fed funds rate (the benchmark overnight bank lending rate) to peak at 3.75-4% by December.

In other news, United Airlines (UAL) has agreed to purchase 200 four-set electric air taxis which it expects to be delivered in 2026. Welcome to the future.

Stocks snapped a three-week losing streak today to close meaningfully higher 😅

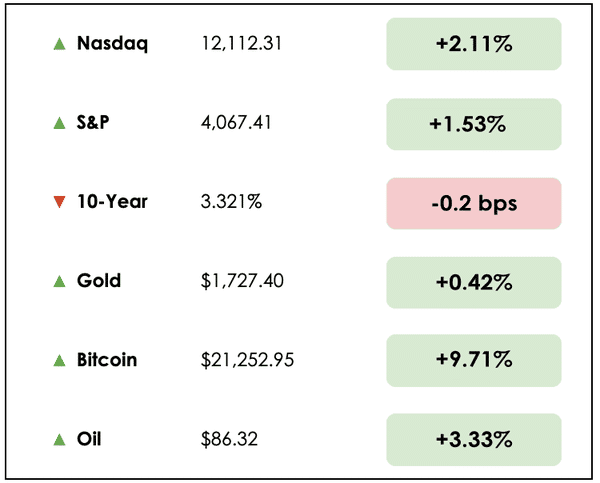

Here’s the market rundown:

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Optimism around peak inflation, earnings resilience, and a strong labor market dominated the bullish narrative for the day, though with the prospect of a Fed committed to higher rates, this feels like mostly just a bear market bounce.

Today, we’ll discuss fighting over a $6.6 trillion market, big moves from Tesla, criticisms of carbon offset markets, and illusory equity premiums.

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Let’s dive in! ⬇️

IN THE NEWS

👀 Vanguard Closes In On BlackRock In $6.6 Trillion Market (FT)

Explained:

- In the massive ETF market in the U.S., two asset management giants fight for supremacy over passive funds. At the end of last month, Vanguard’s ETF assets under management (AUM) totaled $1.84 trillion, while BlackRock’s (BLK) iShares unit held $2.21 trillion.

- In terms of attracting new money into the space, Vanguard has prevailed and is on quite the hot streak. In August, it received four times more inflows than its rival. In just 2019, BlackRock’s AUM advantage was 50% larger.

What to know:

- 15 out of 16 of the largest ETFs are offered by either BlackRock or Vanguard. In this rapidly growing space, the two companies disproportionately dominate. While BlackRock offers over 1,300 ETFs globally, Vanguard has just 82, and it hasn’t launched a new one in two years.

- Mutual fund and ETF fees have dropped dramatically over recent years, as these two firms engage in a race to the bottom, since they have few other metrics to compete on. To the long-term investor, this has been a great development.

🚗 Tesla Consider Lithium Refinery In Texas (Reuters)

Explained:

- On the gulf coast of Texas, the popular electric vehicle producer, Tesla (TSLA), is looking into establishing a lithium refinery that would secure supplies of key components for its batteries. Tesla has touted that the battery-grade lithium hydroxide refining facility would be a first of its kind in North America.

- While the move would be quite significant for its supply chain management, the company has said its decision to invest in Texas will be based on its ability to receive relief on local property taxes.

What to know:

- Lithium is a necessary input in Tesla’s cars, though supplies of the metal are scarce, as are refining capacities for it. To hedge lithium price surges due to rising electric vehicle demand broadly, the company’s CEO, Elon Musk, has suggested previously that Tesla may need to enter the mining and refining industries directly to maintain a competitive advantage.

- If approved, construction on the project could begin as early as next quarter.

- China remains the world’s largest lithium processor, but with Sino-U.S. tensions rising, companies like Tesla are hoping to establish backup plans.

❌ Large Number Of Carbon Offsets Don’t Cut Emissions (WSJ)

Explained:

- The market in so-called voluntary carbon credits has enabled corporations globally to, in theory, offset their carbon emissions by funding projects elsewhere in the world that plant trees, invest in renewable energy, save endangered forests, etc.

- The hope is that large greenhouse-gas emitters, like airlines and industrial companies, invest in green projects that, otherwise, wouldn’t have been feasible. But researchers have found that, in reality, such initiatives better illustrate established companies simply transferring money to each other through carbon credit purchases and sales.

- If, for example, a green energy project would have happened anyways, but a large airline purchases carbon offsets from the green energy producer to “fund” its development, then the net result is not actually a neutralization of additional carbon output.

What to know:

- Demand for carbon credits has soared, as it enables companies to conveniently reach, on paper, carbon-emission goals without any fundamental changes to their operations. More than 5,000 companies have signed a U.N. pledge to eliminate or offset their emissions by 2050.

- The voluntary market for carbon credits is expected to grow up to $180 billion in size annually over the next decade. With large government subsidies already powering many renewable energy industries around the world, it’s worth considering whether this market for carbon credits is genuinely reducing carbon emissions.

- The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission has said, “Concerns about transparency, credibility, and greenwashing may hamper the integrity and growth of these markets.” And United Airlines’ (UAL) CEO has even called these voluntary carbon offsets “borderline fraud.”

DIVE DEEPER: ILLUSORY EQUITY PREMIUMS

The basics

In order to earn a return on your money, you must take risks with your investments. This concept underlies finance 101, and different types of risks will shape your expected return.

The logic is sound, for if we think of risk as being the uncertainty and time (opportunity cost) associated with a given investment, generally, as the uncertainty of receiving your capital back increases, so does the compensation you demand in return.

You earn essentially nothing on your bank savings deposits, because, well, you take no risk. That money is guaranteed by the FDIC, and banks manage it ultra-conservatively. You do earn a small return though, and this primarily reflects the time cost of money, rather than other forms of risk.

Bonds

Bonds typically offer a somewhat higher return, since you do incur credit risk, though even these returns remain relatively muted as lenders are at the top of the capital stack.

What that means is bondholders are given priority over stock investors, who own the company’s equity, during bankruptcy. Debts are paid back first, and what remains goes to equity holders.

So from a 30,000-foot view, bonds broadly offer lower returns than stocks, because bond investors are more likely to get their money back which reduces uncertainty and correspondingly risk.

Expected returns

How do we determine, then, the appropriate risk premium for owning stocks?

In other words, how much additional compensation, relative to more certain forms of investing, should stock investors expect?

The short answer is that this is a dynamic and nuanced calculation, but there are some interesting ways to think about it.

Let’s discuss.

Breaking it down

One partial explanation, according to the famed hedge fund manager and author Antti Ilmanen, for why expected equity returns vary, relates to the business cycle. As we reach peaks and troughs in the cycle, companies’ financial positioning changes dramatically.

At the trough (the lowest point in a recession), companies’ operations, and therefore their profits, which is what matters most to equity investors, are at their greatest uncertainty.

The economy is in poor shape, sales are likely declining, credit risks are rising, and fearful sentiment crescendos. At this point, stocks will bottom at a level where investors feel appropriately compensated for economic risks and are willing to step back in as buyers.

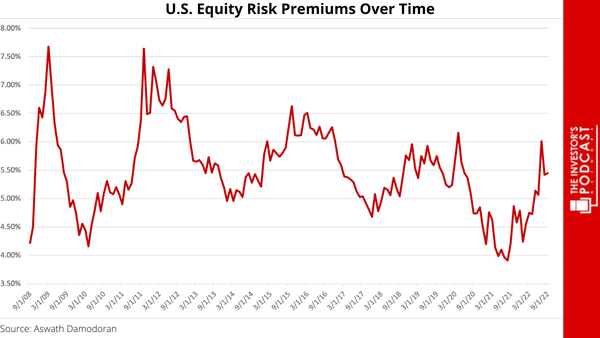

Basically, when things are their worst, market participants are most risk-averse, which actually means expected returns (equity risk premiums) at that point in time are their highest.

The same happens at the business cycle’s peak. While the economy is at its strongest, this is, counterintuitively, the worst time comparatively to be investing.

Investor enthusiasm, fueled by thus-far strong economic fundamentals, amplifies rising valuations for stocks and can even create bubbles. Given the euphoria, empirical evidence has shown that at these points in time, equity risk premiums hit their lowest, as investors become (delusionally) certain that their bets will pay off.

When deriving your own expected return estimates, then, you’ll want to consider just how fearful or exuberant the market is.

So how have equity premiums looked over time?

Equity premiums are pretty high around the world, but this is only true for long periods of time. For entire decades, stocks have underperformed bonds and even cash.

This is hard to wrap your head around, so we’ll say it again.

Can you imagine patiently waiting in the stock market, to build your wealth, for over ten years just to break even?

That’s an incredibly long time for even the most staunch buy-and-hold investors to not be properly compensated for their incurred risks.

On the other hand, there’s actually a phenomenon known as the equity premium puzzle, which states that stocks have historically had excessively high outperformance relative to lower-risk investments like Treasury bills.

Financial academics believe that equity investors have, over the years, been compensated at rates far beyond their corresponding risks.

While the historical equity risk premium has ranged between 3% and 7%, these theorists propose that relative to economic consumption and growth that’s much more stable each year, such excess returns aren’t warranted.

Takeaway

Understanding why equity risk premiums exist, especially at levels that exceed fluctuations in the real economy, is critical to those planning on allocating to stocks long-term.

Without an understanding of the underlying factors driving these returns, how can one hope to act should circumstances meaningfully change?

For example, stock market declines have, at times, matched almost the entirety of a working person’s life. U.S. market indices didn’t recover their lost ground until 1954 after the infamous 1929 crash.

In some cases, for countries that suffered defining political and military defeats, it can take far longer for markets to recover. In the case of Austria, this was more than 90 years.

U.S. Bias

This raises the concern that our commonly held beliefs surrounding the seeming certainty of positive equity risk premiums and, correspondingly, excellent stock market returns, may be significantly distorted by survivorship bias in the U.S.

While the United States emerged victorious from two world wars and the cold war as one of the planet’s greatest economic powers, it’s no surprise that its stocks have performed fabulously. But this equity performance cannot be easily extrapolated to other countries’ markets that did not bear the same advantages.

Look no further than Japan for historical precedent. In 1989, its stock market was the largest in the world, and it’s gone over 30 years since, as measured by its signature Nikkei 225 index, without meaningfully positive returns.

So, then, we must consider whether the significant equity risk premiums seen in the U.S. are the exception or the rule for stock investing generally.

What to know

For all investors, questioning our assumptions about markets is quite important. American investors, in particular, are susceptible to a survivorship bias in domestic markets that’s, in many ways, a statistical outlier from the equity investment returns across history for other societies.

At the same time, the belief that “stocks must go up”, is very common in the U.S., and many retirement portfolios are constructed on this notion.

Understanding the nature of equity risk premiums then, both domestically and globally, is imperative to our long-term investment decisions.

It’s hard to say whether the equity premium puzzle will continue, but one thing should be clear, long-term losses in stocks are a real possibility.

The honest truth is that just because you hold patiently for many years, doesn’t mean you will earn positive real returns, let alone match the precedent for returns set in the U.S. across much of the past century.

Wrapping up

In our assessment, this raises the case for value investing more than ever. While entire markets and indices may lag for decades, as is seen both globally and in the U.S., there will still be individual winners and great businesses to own around the world.

Know what you own down to the most fundamental drivers of returns, and diversify accordingly. This is, at least, how investors seeking to preserve and build wealth across generations think.

To be clear, the message here is not to avoid equity risk altogether. It’s really about framing expectations and remembering to exercise caution when allocating your life’s investment portfolio.

“Stonks” are not guaranteed to go up, especially if a country faces economic disasters. The U.S. has been able to mostly avoid such events, which explains the belief that investing here is less risky.

This, in reality though, likely lowers forward expected equity risk premiums, and may yield investors myopic to the true risks they’re taking by participating in the stock market.

Tell us — What do you think of our take on equity risk premiums and the risks of stock investing?

For more on risk premiums in investing, we’ve written about the topic previously.

You can also visit the academy section on our website for more educational resources.

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

See you later!

If you enjoyed the newsletter, keep an eye on your inbox for them on weekdays around 6pm EST, and if you have any feedback or topics you’d like us to discuss, simply respond to the email.